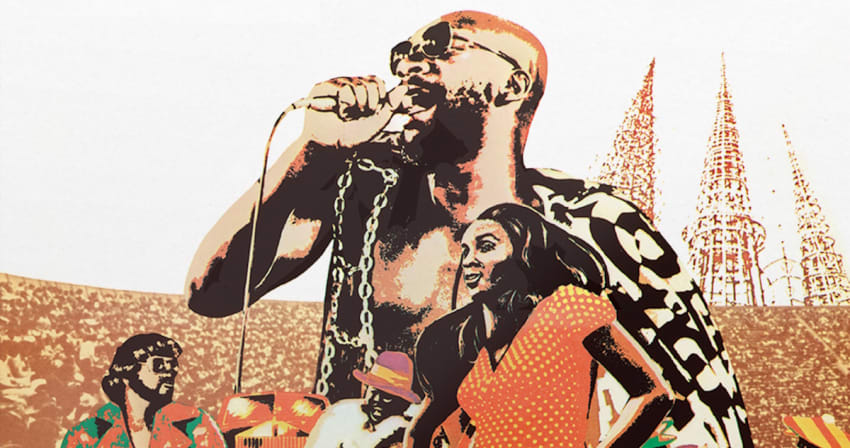

A 6-Hour Soulful Expression In Front Of 100,000 People: The Landmark 1972 Wattstax Concert

Revisit the 1972 all-star concert featuring the soul music of Stax Records in recognition of Black History Month.

By Andy Kahn Feb 22, 2024 • 1:43 pm PST

An estimated crowd of over 100,000 people came together at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on August 20, 1972 for a daylong concert billed as Wattstax. The historic event drew one of the largest crowds of the time and showcased many of the era’s premier Black musicians.

Organized by Stax Records, a prominent Memphis-based record label that was at the forefront of popularizing soul music, Wattstax emerged as a significant cultural and historical moment. The lineup for Wattstax was nothing short of legendary, featuring a stellar array of musicians. The performances, primarily by artists on the Stax label, honored the rich musical heritage of Black American music in the form of gospel, blues, soul, rock and R&B.

Advertisement

Like other historic concerts of the era – Monterey Pop, Woodstock and Altamont (but unlike the Harlem Cultural Festival) – a feature-length documentary film capturing Wattstax brought the historic concert to an even wider audience beyond the impressive numbers who gathered in Los Angeles that day in 1972. Released in 1973, the documentary film of the same name directed by Mel Stuart captured the essence of the concert, blending electrifying performances with intimate interviews and footage of life in Watts.

Through its innovative combination of music and social commentary, Wattstax the film became a capsule of Black music and an important example of the power of community. In 1974, Wattstax earned a Golden Globe nomination for Best Documentary Film.

The circumstances that led to the Wattstax concert were detailed in a press release celebrating the 50th anniversary of the event and documentary film.

On August 11, 1965, a 22-year-old Black man named Marquette Fry was pulled over by white police officers on suspicion of driving while intoxicated in the Watts community of Los Angeles, igniting the protests that would come to be known as the Watts Rebellion. This breaking point was spurred by the destitution of Watts residents, who had grown weary after decades of discrimination, lack of jobs with decent wages, and other forms of economic oppression, political isolation, poor schools, unfair housing practices, and the type of racial superiority that had long denied them their right to live happy, fulfilled lives.

In the South, during the same time, Stax Records President Al Bell witnessed angry white mobs, the intervention efforts of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, white children jumping out of school windows to avoid contact with the Black children, and the throwing of burning toilet paper on to the Black children.

In 1971, Bell set up a Stax satellite office in Los Angeles and regularly monitored the living situation in Watts and the positive changes in the community, or, more accurately, the lack thereof. It seemed the residents of Watts had lost all hope, like a people on the verge of suicide. They had resigned to accept the loss of the battle for basic acknowledgement and a fair quality of life. Bell knew something had to be done to change this and was certain that healing could be delivered through the power of music.

“I believed then that soul music is an art form born of the African American culture, and that Stax should support the people who supported us,” Bell stated. “I also wanted to garner more recognition for our roster of Southern soul artists by taking them to Hollywood for a performance that no one would ever forget.”

According to NPR, Wattstax concert ticket prices were only $1 for entry to the all-day event and upwards of $70,000 from the sales were donated to the Sickle Cell Anemia Foundation, the Martin Luther King Hospital in Watts, Watts Labor Community Action Committee and the Watts Summer Festival.

“It was a celebration of the African-American experience and a testament to the transformative power of music,” Bell told NPR. “You see 5 and 6-year-old kids. You see mothers; you see fathers. You see grandfathers, grandmothers. It was like a family reunion. I mean, it was like a church service; the same kind of feeling and interactions took place there. There was one spirit and attitude that prevailed. It was the spirit of love.”

Advertisement

Wattstax was headlined by Isaac Hayes, whose funky “Theme From Shaft” (from the soundtrack to the film of the same name) had just won an Academy Award for Best Original Song, the concert also showcased performances by Rufus Thomas, Carla Thomas, Albert King, and many others.

The Staple Singers, who also performed at the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival that was also called the “Black Woodstock,” were also on the Wattstax lineup, which some gave the same moniker. Civil Rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson, who also appeared at the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, was also onstage at Wattstax. ‘

The concert kicked off with a stirring rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” by Kim Weston, which was followed by Jesse Jackson leading the crowd through a powerful recitation of “I Am Somebody.” Weston then performed “Lift Every Voice And Sing,” which is often referred to as “The Black National Anthem.”

Among the other notable highlights were The Staple Singers delivering a powerful rendition of “Respect Yourself,” Rufus Thomas’ dynamic performance of “Do the Funky Chicken,” blues guitar legend Albert King dazzling the audience with his soulful “I’ll Play the Blues for You,” Carla Thomas’ soulful rendering of “Gee Whiz (Look At His Eyes)” and Stax Records’ house band The Bar-Kays laying out the funk classic “Son Of Shaft.”

As the sun set over the Coliseum, Isaac Hayes took the stage in dramatic fashion, donning his signature gold chains and sunglasses, and delivered an unforgettable performance that reached a peak with the aforementioned “Theme From Shaft.”

Theme From Shaft

In 2020, the Wattstax documentary film joined the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress after being deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” Comedian Richard Pryor introduced the documentary, setting up the groundbreaking film by stating:

“All of us have something to say, but some are never heard. Over seven years ago, the people of Watts stood together and demanded to be heard.

“On a Sunday, this past August at the Los Angeles Coliseum, over 100,000 Black people came together to commemorate that moment in American history. For over six hours, the audience heard, felt, sang, danced and shouted the living word in a soulful expression of the Black experience.

“This is a film of that experience and what some of the people have to say.”

Watch the Wattstax documentary film and stream the live album culled from the historic concert below: