From Spirituals To Swing: The Historic Carnegie Hall Concerts

Revisit a pair of groundbreaking concerts in recognition of Black History Month.

By Andy Kahn Feb 1, 2024 • 12:41 pm PST

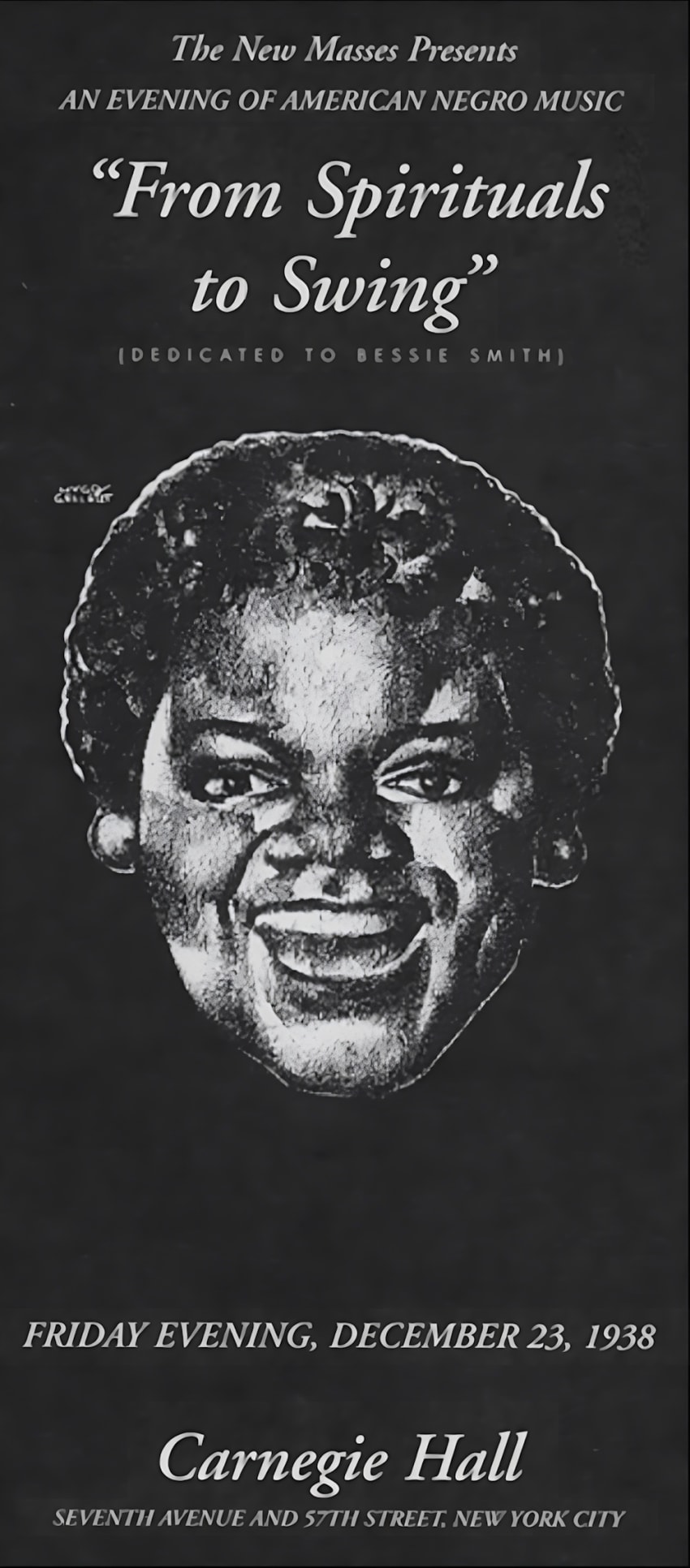

In 1938 and 1939, Carnegie Hall in New York City hosted two groundbreaking concerts curated by the visionary producer John Hammond. Officially billed as An Evening of American Negro Music, “From Spirituals to Swing,” these concerts marked an important milestone for Black musicians in America.

Hammond advocated for racial integration in the arts and envisioned bringing the music of Black performers to mainstream, mostly white audiences. Hammond was a highly influential record producer known for his significant impact on the music industry during the 20th century. Renowned for his talent-spotting ability, Hammond played a crucial role in discovering and nurturing the careers of iconic musicians such as Billie Holiday, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Leonard Cohen, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Ahmad Jamal and many others.

Advertisement

The From Spirituals To Swing concerts helped bring recognition to Black musicians whose influence continues to be felt decades later. Hammond designed the concerts to showcase the rich tapestry of Black music by presenting a comprehensive narrative from its roots in spirituals and blues to the emerging swing and jazz movements.

Hammond recounted the first concert in the Vanguard Records’ liner notes for the live album that came out several years later, writing:

“It was on December 23, 1938, that the first Spirituals to Swing concert was given at Carnegie Hall. For many years it had been an ambition of mine to present a concert that would feature talented Negro artists from all over the country who had been denied entry to the white world of popular music. Several groups reluctantly turned down the idea, before the final sponsors showed up, arrangements were made, and the dream became reality …

“The first concert was a chaos, sold out, and an enormous success with the audience. An overflow crowd of some 300 had to be seated on the stage, which contributed to the confusion …

“One of the greatest of all jazz artists, Bessie Smith, had died tragically the year before, and it was to her memory that the first concert was dedicated. A niece by marriage, Ruby Smith, was found and sang Bessie’s songs with her old accompanist James P. Johnson at the piano. The emphasis was on blues, and except for the gospel groups, all the artists concentrated on that art form, which had very little popular recognition in the year 1938.”

The program featured a performance by the Count Basie Orchestra whose members included its namesake bandleader Count Basie (an early Hammond discovery) on piano, Lester Young on tenor saxophone, Buck Clayton on trumpet, Walter Page on bass and Jo Jones on drums, who also performed as the Kansas City Six.

The first From Spirituals to Swing concert also featured performances by Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the gospel and blues singer known for her innovative electric guitar playing and captivating vocals. The lineup included bluesmen Jimmy Rushing, also known as “Mr. Five by Five,” who was a blues shouter and deep-voiced jazz singer, Big Joe Turner — another blues shouter known for his powerful singing style, and Big Bill Broonzy, the blues guitarist and singer known for his contributions to the Chicago blues scene.

Others who performed include stride piano innovator James P. Johnson and boogie-woogie piano players Meade Lux Lewis and Albert Ammons. Adding a rural blues element to the program was the duo Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee.

Big band and swing era jazz was represented by vocalist Helen Humes, trumpeter/vocalist/bandleader Hot Lips Page and the New Orleans Feetwarmers. The 1938 concert at Carnegie Hall also saw performances by the influential gospel group known for their soul-stirring harmonies, Mitchell’s Christian Singers. View a list of performers here.

Further describing the first concert, Hammond recalled:

“An enormous amount of work went into the preparations for the event. Artists had to be brought from enormous distances, financing had to be arranged. On one trip to North Carolina I was accompanied by a struggling young composer named Goddard Lieberson (now president of Columbia Records), where we were the guests of Jimmy Long, a talent scout for the American Record Company and wonderful host. This accounted for the presence of Mitchell’s Christian Singers, the first authentic gospel singers to be presented in a New York concert, and the extraordinary Sonny Terry.

“Robert Johnson, Vocalion’s blues singer and guitarist, was signed, and then was promptly murdered in a Mississippi barroom brawl, whereupon Big Bill Broonzy was prevailed upon to leave his Arkansas farm and mule and make his very first trek to the big city to appear before a predominantly white audience.”

Sister Rosetta Tharpe & Albert Ammons – That’s All

The second installment of From Spirituals To Swing was held on December 24, 1939. Howard University’s Sterling A. Brown served as the emcee of the Christmas Eve concert. Prof. Brown, a noted poet and blues authority, began the evening by providing an invocation that introduced the program, a portion of which is excerpted (from the Vanguard Records liner notes) below:

“‘From Spirituals to Swing,’ as the program notes explain, is not a tracing of evolutionary steps. It is not giving what existed a score of years ago, but has its own exciting validity today. It is not within my province or power, and probably not within your patience. for me to give a history of the music of the American Negro. I should like to give, however, let’s say, is capsule of this history.

“Let us gaze for a brief moment at the past. Legends say, and the documents of the slave trade establish, that in the terrible middle passage slaves were brought on deck for air and exercise and were bidden to sing. And they were lashed into singing happy songs, lashed into singing that which would keep them from brooding. Without too great a fancy, one cannot conceive here the general idea of the minstrel nonsense gay jingles. The harried captives, however, could not sing. or could not feel these forced songs in this strange floating world. Deep in the hold, away from the watchfulness of the sailors and the captains, they could sing their own songs in their own way and they could moan deep in the dark and crowded holds, the black man’s trouble in a strange captivity.

“In the spirituals of slavery, the spirituals expressed what Christianity had taught these slaves. It expressed, of course, their resignation (‘Bye And Bye Gonna Lay Down This Heavy Load’, it expressed ‘Keep Me From Sinking Down,’ it expressed sometimes the joyful escape (‘I’m Goin’ To Feast At The Welcome Table,’ ‘When The Saints Go Marchin’ Home’) or it expressed the despair of a blind man who stood on the road and cried. Or it expressed and accepted ‘I Don’t Know What My Mother Wants To Stay Here For; This Old World Has Been No Friend To Her.’

“But it likewise had its urgent challenges: ‘Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel, Why Not Every Man,’ or that clarion call ‘Go Down Moses, Way Down Egypt Land, Tell Old Pharaoh to Let My People Go,’ but side by side with these spirituals, of course, we have the breakdowns, the jigs, the syncopation of ‘Juba-this, Juba-that, Juba Skin The Alley Cat.’

“‘Old Aunt Dinah She Got Drunk, Fell In The Fire And Kicked Out A Chunk,’ or the sardonic ‘My old Missus Promised me Before She Died She’d Set Me Free, She lived so long till her head got bald and she give out with the Notion of Dyin’ at all. My Old Master Promised to me before he died he’d set me free, but my old master’s Somehow Gone and he left me Hillin’ Up the Corn. Yes, Old Master Promised me, but his papers didn’t leave me free; a dose of pizen helped him along, may the Devil preach his Funeral Song.’ Which I submit to you is something of a grandfather for Louis Armstrong’s ‘I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal You.’

“We have likewise crossed the very glorious songs of John Henry, the epical hero of the Negro working class, who died with his hammer in his hands, and one version of this song we shall hear tonight.”

Advertisement

Building upon the success of the previous year, the 1939 program included the groundbreaking Benny Goodman Sextet with Black guitarist Charlie Christian and vibraphonist Lionel Hampton. Goodman’s concert on January 16, 1938 was the first time Black and white musicians performed together on the Carnegie Hall stage, which was a powerful statement during the era of segregation and institutionalized racial discrimination.

Performers from the first From Spirituals To Swing concert that returned for the second year included Big Bill Broonzy, Albert Ammons, James P. Johnson, Helen Humes, Kansas City Six, Count Basie And His Orchestra and Sonny Terry (who performed “The New John Henry” with Bull City Red). The second concert also presented performances by the Golden Gate Quartet and Ida Cox.

“In short, the second ‘Spirituals to Swing’ was better organized, equally profitable, and perhaps a shade less exciting than the first,” Hammond assessed. “Although its reception was every bit as enthusiastic.”

A summary of the historical impact the From Spirituals To Swing concerts — measured several decades ago — was written for the later issued live album whose liner notes have been previously cited. Within the notes was an essay written by noted jazz critic Charles Edward Smith. Titled, A Gateway In Time: The Spirituals To Swing Concerts, the essay conclude with this passage:

“Without being planned to prove a point, these concerts demonstrate that the Southwest — as a focal point for what was going on in many parts of the country — was a gateway in time — the gateway to contemporary jail. By the early 1940s wide areas of jazz were being revitalized by contact with the sounds from this area — Mary Lou Williams, Count Basic, Jimmie Lunceford, Lester Young, Charlie Christian and, finally, Charlie Parker — to mention only a few of those who were responsible, to a large extent, for a reaffirmation of the blues and the beat.

“The Count Basie Orchestra brought the blues, the life blood of jazz, into a style of swing that made use of its basic elements in orchestral terms. If, with this in mind, you listen to Bill Broonzy and then to Bill Basie’s band, you’ll discover these relationships for yourself. And one might say that the urban blues singer with a band — Joe Turner shouting over the noise of a Kansas City saloon — is a connecting link.

“So is the walking bass that produced boogie woogie, or its earlier counterpart, before any of us were born —and that ‘walked’ all over this land of ours, from San Juan Hill and James P.’s Mule Walk to the Basie bandstand and Walter Page. ‘The Big One,’ with that big bass, Pagin’ The Devil, And, finally, with these performers — from the quaver of the blues to the linear line — it walked right into Carnegie Hall.”

What made the From Spirituals To Swing concerts historically significant for Black musicians in America was the platform they provided for showcasing their immense talent to a largely white audience at Carnegie Hall. At a time when racial segregation was deeply divisive in America, the From Spirituals To Swing concerts served as a glimmer of inclusivity, bringing together audiences from different backgrounds to hear the brilliant music made by Black musicians.

The success and critical acclaim of the concerts helped pave the way for increased opportunities and visibility for Black musicians, influencing the subsequent evolution of jazz, blues and popular music. The performances demonstrated that Black musicians were not limited to specific genres but were masters of a wide range of musical styles. The integration of Black and white musicians on the same stage challenged the societal norms of the era and contributed to the ongoing struggle for racial equality in the United States.

Advertisement

Listen to a recording of the second From Spirituals To Swing concert: