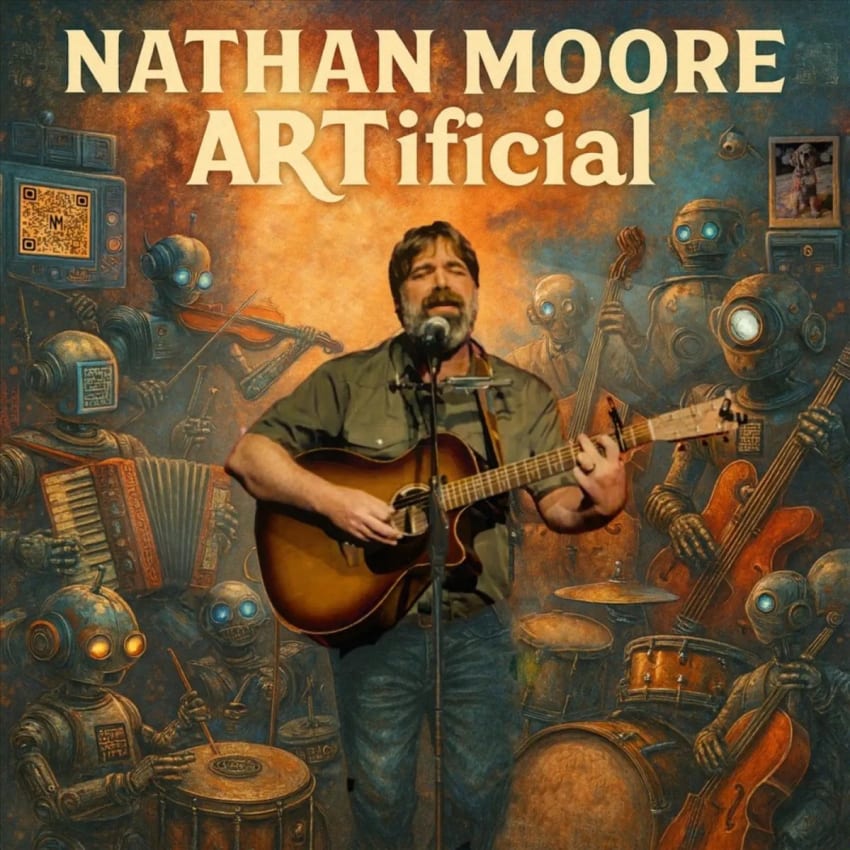

Singer-Songwriter Nathan Moore Talks New AI-Assisted Album ‘ARTificial’

‘This record is not me saying, ‘Yes.’ It’s more like me asking, ‘Huh?’

By Matt Hoffman Oct 13, 2025 • 12:24 pm PDT

In the ongoing debate over what constitutes “the real thing,” few analogies are as potent as that of natural versus lab-grown diamonds. Is something’s value derived from its origin, its “aura,” to borrow a term from Walter Benjamin’s iconic 1935 book, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction; or does it begin and end with function and aesthetics?

In 1974, Robert Pirsig introduced his seminal Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance with a similar dichotomy between “romantic” and “classical” views of value, and the same debate remains alive and well in modern music.

Many analog purists see the world differently from digital pragmatists, and the arrival of artificial intelligence has pushed this conflict to its extreme. In the world of modern songwriting, then, if the entirely artificial Velvet Sundown is arguably an early example of a “lab-grown diamond,” then Nathan Moore is the quintessential “natural diamond,” sans the blood-related ethical questions.

Known for his decades of work with pioneering folk rockers ThaMuseMeant and super hodgepodge Surprise Me Mr. Davis, Nathan Moore is a veteran, award-winning troubadour whose art is the product of lived experience: organically grown on the road and rooted in a deeply human, analog tradition. Recently, he spent years cultivating what he called “the Daily Practice,” where he would livestream himself playing his own tunes, taking requests from members of his Discord server (or anyone else who happened upon the show on his YouTube channel).

This makes his latest album, ARTificial, just released on his 55th birthday, such a fascinating provocation. Using an AI-powered tool to produce fully-formed arrangements of songs he wrote the old-fashioned way — on an acoustic guitar — Moore has created a stunning collection of “lab-grown” music, challenging assumptions about the definition of “art” in the age of artificial intelligence.

In doing so, Moore has become a seemingly unlikely test pilot flying at the intersection of authenticity and artificiality, exploring whether a sound with no human hands behind it can still have a human heart; at the same time, you could say there’s nobody better to explore the boundaries.

You’ve been a professional musician your whole adult life. What dream were you chasing when you started out?

My dad had this huge 45 record collection that was one of my favorite toys beginning when I was 7 or 8. I was immediately aware of everything from the ‘50s, ‘60s, and then I was in the ‘70s and became a teenager when MTV launched, so when I went out pursuing my dream of being a musician, a songwriter, and making it in the music world, the dream always was like, “All right, so you go out, either by yourself or you form a band, then you get people to like your sound, and then record labels find you. Then you get a record deal where you go into a studio, they produce your record, then the world responds to the record. Hopefully, they love it, and you get to make another one.” And so it was a very pretty traditional dream that I feel blessed to have been able to so genuinely make a life of pursuing.

I grew up in Staunton, Virginia, the home of The Statler Brothers, initially Johnny Cash’s band, who then went on to become one of the biggest country acts. They would throw a huge celebration every Fourth of July, and the population of Staunton would grow from 20,000 to 400,000 for a weekend. And these guys were from Staunton — everything in my life said, “This is possible. Go get ‘em. You can do this!”

How do you think about that now, with the benefit of a career’s worth of hindsight?

Everything I dreamed of as a child came true. I formed a band, made records, heard us on the radio, and toured the country in a tour bus, except we never got put in the studio with George Martin or whoever it was that would polish our sound to perfection. So much of the music we love are records by artists who were produced by a major label to make them sound that certain way, but pretty much every record I ever made was self-produced by the band and the engineer.

There was only one time we got to work with a producer, when a potential manager wanted a polished recording to shop around. They put us in this professional studio, brought in Bob Dylan’s keyboard player, and a producer. He told us what to do. “You do this, you do that… again!” He decided how the tracks would ultimately sound. And when we heard the finished product, I was like, “Holy moly, who the hell is that?” And it was awesome.

As I put together my new album, ARTificial, being in headphones and singing to AI-generated, professional-sounding productions of my songs, that’s the place I’ve been trying to reach my whole life. That’s what I’ve always wanted to do: to be in the studio making the records, singing my songs to rich orchestration that’s as grand as what I hear in my head when I write them. That childhood dream.

How did you discover this AI tool that ultimately became your “producer” for this new record?

I’d messed around with AI production tools early on, where it would generate music based on text prompts. I thought it was pretty amazing, mostly good for a laugh, but I got bored after a couple of days and forgot all about it. Then months later, I saw an ad where someone uploaded audio to it: he basically hammered out something in his kitchen, uploaded it to the service, and it made this pop production of exactly what he played.

And I was like, “Holy cow, wait a second.” So I immediately ran down to the basement and uploaded one of my songs.

What was that first experience like? When you uploaded your own song and it came back with a full arrangement?

It came back immediately with this fully produced, like full “Paris jazz in the ‘20s” vibe, doing my little guitar hook, on pianos and clarinets: it was really profound. I’d become fanatical about learning to self-produce over the last 10 or 12 years, trying to be patient because there’s the whole “10,000 hours to mastery” idea in learning a craft. But when it comes to making a record, I think you also have to spend 10,000 hours engineering, plus 10,000 hours playing all these instruments, knowing what specific drums are really supposed to do, etc.

I’ve always been a prolific songwriter, so it was a really cool dream to be able to make radio-quality versions of my songs myself. I was blindly, ignorantly trying to do something that there was no possible way I was going to be able to achieve on my own. Sometimes it takes 10,000 hours to find out you actually suck at something. I was only willing to admit that to myself the last couple of years. So really, when I first heard this back, it was pretty cool.

How did it compare to the Moorechestra, where you would invite fans to bring instruments and play along at your shows? Is this project like the ultimate, high-fidelity realization of that same impulse?

My songs have always sounded sort of like this in my head, but I’ve struggled to explain it. It actually became a bit that I would do during my shows. I’d come out of the end of a song, my eyes would have been closed, I was in this fantastic landscape, and it was weird to end a song and just be in this room with these people. So I’d say, “Man, I wish you could hear what it sounds like in my head.”

Then, during the Hippy Fiasco Rides Again tour, I encouraged people to bring instruments to my shows and accompany me from their seats: they became the “Moorechestra,” and it happened tons of times, where the audience was the band. The whole thing was just all out of wanting the world to hear how big the songs sound to me. Because how they sound to me is definitely not just a dude with a guitar.

How do you “collaborate” with the AI to get the sound you’re looking for?

It started with a lot of trial and error. I would upload the track and get back something that wasn’t “it,” so I would try it again and notice, say, “Oh, it’s really latching on to that one part of the song. I don’t like how it’s latching on to what the bass is doing, or that fiddle part, so let me try something different.”

I would open that demo session, mute stuff or accentuate parts, and then re-upload it until I got what I wanted. For the song “Rubber Ball,” I didn’t like a single version it gave me when I fed it an old session file. And then on a whim, I just grabbed my guitar and all I told it was the guitar hook with the vocal, and immediately got back what I wanted to hear. So as you do it, it gets really obvious what it’s going to do with what you give it.

Some people have asked me if I would include the tracks I uploaded as the blueprints for the AI versions. But a lot of the demos aren’t really listenable because their sole purpose was to give the tool what it needed to give me back my songs the way I wanted to hear them, which is a very different thing. For most of the songs, it didn’t take too many tries to get back a version I loved.

I think the things that kept me from being a good producer and a good engineer also prevent me from having that kind of hyper-critical thing: I’m really receptive to the collaboration, which makes it that much more thrilling when I land on something I love. Sometimes, I would like parts of one version and other parts of another, and I would Frankenstein them together in my studio.

Can you share an example of a time the process led to a completely unexpected or surprising result?

The first thing I thought of was an unexpected way I got the right result. There’s this new song called “Blessed Porcupine.” I really like this song, and I fed it in there, and I must have generated 10 different versions, and none of them were “it.” It was even consistently playing the wrong changes. So then I tried a different version of it, re-recorded a version of it to try to be more explicit, and it still wasn’t right.

All of a sudden, just out of frustration, I typed “Bulgaria in the ‘40s” in the text prompt, and the next version back was like, “Bam!” And when you hear it, it just sounds like a cool little indie rock track. It doesn’t have any old far-away vibes. It was really like an angry prompt, and I don’t even know why I said that, but it knew exactly what I meant. And hearing that was like, “What? That worked? Holy shit!”

Has using an AI tool changed your view of a song’s core identity? Is it the lyrics, the melody, or something that exists independently of its arrangement?

My instinctual answer is that a song is an individual that is born fully formed into the world, like a person. It goes the way it goes. Last night, some friends and I picked a 10-minute-long bluegrass-y version of “Frère Jacques,” and everybody there, even the kids, knew that one. We could’ve played it as jazz, rock, Latin, punk or polka. No matter what, somebody is going to sing “Frère Jacques, Frère Jacques, Dormez-vous? Dormez-vous?” Any of these new AI arrangements, or any covers for that matter, are only going to work if we can recognize that individual in it.

It’s still the individual song that’s waving its magic wand and making the moment interesting. That initial birth of the song is pretty consistent, and I can’t see that ever really changing. That moment when a songwriter creates it, that birth of the song, is the magic moment, and anybody that’s written a song knows it. It’s like, “Wow, where did you come from?” Can AI do it? Well, it already does. Badly, but still.

One eternal difference between the song a songwriter writes and a song generated by AI is that the first one has, guaranteed, at least one person that actually cares about it. That’s something.

What was it like to run older songs through the tool vs. newer ones? How did you choose the tracklist for ARTificial?

When I started playing with the tool, I was just like a kid in the sandbox. I just wanted to hear what it did with everything: first this one, then that one, then another. At this point, I’ve got 45 or so different AI-enhanced tracks in the All Access section of my website because I was just having a lot of fun and creating a lot of them.

I like a lot of the versions of old songs that came from quirky prompts like “Play it in the style of a dust bowl string band from the early 1900s.” At first, I thought I would just put out sort of a sampler of the possibilities. Each track in really different styles. But then slowly, it sort of became an actual record, and I loved that moment when I realized that’s what it wanted to be. The music knew what it wanted: I just had to figure out how to put it together.

Most of the songs are the newest I’ve written, and it’s wild how using these AI tools fits thematically with some of the lyrics. The opening track on the record is a song called “Just Isn’t Me,” and the last verse goes: “I don’t play a mean clarinet or dobro or piano, I don’t play a mean anything, really. It just isn’t me.”

So it’s trippy that I’m putting out this record ARTificial where I’m not really playing, and it’s self-referential to the project before the project even existed. It almost feels like the brand new songs were made just for this record, which is pretty cool because I wrote them just before I knew this technology existed.

You’re being very transparent by calling the album ARTificial. How are you thinking about the inevitable controversy or skepticism around using AI in a creative field?

I’ve already gotten a little taste of that, which sort of breaks my heart a little bit, but it’s also something I completely understand. I get that there’s just sort of like a mental impasse that a lot of people will experience where they’re just thinking about how it’s AI so they can’t feel the song, and I think that conflict is really unfortunate. It’s sort of like, if you think there’s shit in the soup, it’s done. You can’t really taste it.

I have no desire to fool anybody, and I feel like it would be a betrayal to people to not tell them up front. I’ve thought deeply and had many profound conversations about the pros and cons of AI and will continue to. It’s an exciting and terrifying paradigm-shifting technology. This record is not me saying, “Yes.” It’s more like me asking, “Huh?”

Does it surprise you that you’re among the first of your peers to explore this new frontier?

I feel like one of the reasons I’m a good candidate, like a test pilot for this weird new airplane, is because I’m a little invulnerable to a certain extent. I’ve been the young person with the insatiable drive, but at this stage, I’m more in a place of gratitude and think a lot about my legacy. So in some ways, I can just think of this as a conversation piece, something to foster and inspire conversation. Hearing what AI can do is knowledge, and I feel like hearing it for the first time on a Nathan Moore song isn’t a bad thing.

With your focus on legacy, how would you like to see things play out on the heels of ARTificial?

I think about how my songs are going to be preserved over time, and success on that level is what’s most exciting for me. At the same time, it would be really fun to see this blossom into a new era of performance, where I can pull off this kind of production on stage. It would be so cool to hear a live band perform this record like it was produced. That’s the new dream!

Advertisement

Loading tour dates