Read An Excerpt Of Dennis McNally’s New Book ‘The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies & Created The Sixties’

Preview the newly available book from the best-selling author and former Grateful Dead publicist.

By Andy Kahn May 14, 2025 • 1:31 pm PDT

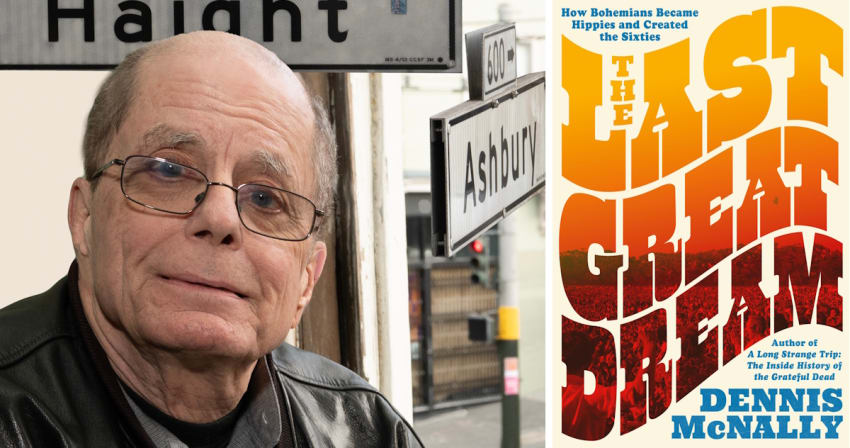

Dennis McNally photo by Susana Millman

In his latest book, The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties, author Dennis McNally explores the circumstances that gave birth to the 1960s counterculture. McNally, who was the Grateful Dead’s publicist for many years, provides a coast-to-coast cultural examination of the post-World War II United States through the actions of prominent artists, authors, musicians and other significant role players.

Having previously published books about Beat Generation icon Jack Kerouac, the Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia, and the role of music and race in cultural development, McNally has proven himself well-versed in the era The Last Great Dream further digs into.

“As a historian, I think that the context of things is ultra-essential, and what shocked me when I started researching is that no one had ever done the backstory, the roots of the sixties,” McNally told JamBase about what spurred the new book. “Even the good books start in 1965. Having touched on the Beats, the Hippies (that is to say the Dead) and then the deeper background (mostly black music) of what made young people up into the ‘50s diverge from mainstream culture… in 2016 I was asked to curate a photo show for the California Historical Society celebrating the 50th anniversary of the ‘Summer of Love.’ About a month into the treasure hunt, I realized it was a book that demanded to be written. And it was fun…”

McNally’s extensive research included conducting dozens of interviews with many people who had first-hand accounts from prominent locales highlighted in the book. One interview was particularly enlightening for McNally.

“About six months before he died (I’m so grateful I got there), I interviewed Mel Weitsman, aa former student at the Art Institute, later a trumpet playing, cab-driving Beat around North Beach,” McNally revealed. “His story took him all the way out of mainstream culture into studies with Zen master Suzuki Roshi, to the point he was later the abbot of SF Zen Center and then the Berkeley Zen Center. But he had a very Beat past which I didn’t really know about until we sat down – a very special afternoon for me. ”

Traversing from the mid-1940s through the turbulent mid-1960s, The Last Great Dream takes readers on a journey from the Bohemian Beatnik era that birthed Beat Generation writers like Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, through other freak movements like the Bay Area hippie scene in the 1960s. Any likely attempt to tell this story is going to have a connection to the music that was so important to the culture at the time. Music, musicians and those who supported them play integral roles in The Last Great Dream.

“Music is the most popular non-verbal (sometimes) way we communicate, and it was essential to this entire story, first with Bop in the ‘40s and ‘50s, then rock and roll, then folk, and finally (having taken LSD), the psychedelic rock that we all understand to be emblematic of the San Francisco scene,” McNally said. “Which is why the book ends at Monterey Pop, where psychedelic music really got introduced to mainstream America.”

McNally also shines a light on the other side of the often maligned early countercultural movement, painting a picture of its lasting influence, rather than the frequently tossed aside assessment of its value. The Last Great Dream presents significant events of the era within a proper historical context.

“The language, dress (flowers, beads, color), and behavior (drugs, looser sexual attitudes) were so unusual (in, say, 1966) that these relatively insignificant qualities became the whole study to the very straight media that covered them,” McNally noted. “They perhaps vaguely understood that something was happening that they didn’t fully grasp, but the spiritual content of hippie, the connection to the earth, the use of LSD as a sacrament – they had no clue.”

McNally blends a documentary-style adherence to a factual record with illustrative anecdotes and personal insights to tell the story of the constantly evolving era.

“I think the overall picture – that poets, painters, mime artists, electronic composers, dancers, and so forth each affected each other, and with the shared experience of psychedelics, brought people to a similar place rejecting the greed and competitiveness of mainstream life,” McNally explained. “It was a much more complicated (which is why it’s a long book) process than people necessarily expect.”

The excerpt below is taken from chapter 26 “More Changes: 1965 in San Francisco and Thereabouts.” The chapter begins with McNally setting the scene in America early in 1965, where the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War and the burgeoning counterculture were at the forefront of society.

McNally describes the formation of scene unfolding in San Francisco with the birth of bands the Charlatans, Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother & the Holding Company, the emergence of psychedelic light shows and posters and the rise of experimental theater leading up to August 1965 — where the story picks up below.

At that time, rock in San Francisco had more to do with a man named Tom Donahue and his partner Bobby Mitchell. Old-school East Coast disc jockeys, they had put a continent between themselves and emerging payola scandals to begin anew at KYA, San Francisco’s leading Top 40 station.

In 1963, they began to promote concerts in the standard format of the era, with perhaps ten acts performing three songs each. Relentlessly entrepreneurial, they started Autumn Records, which had a few hits, including “Laugh, Laugh” by the Beau Brummels, but was most notable for their in-house producer, a talented young man from Vallejo named Sylvester Stewart, later Sly Stone.

Donahue’s next move was to open Mother’s, which he described as “the world’s first psychedelic nightclub,” among the topless joints on Broadway. Donahue had hired hip beatnik woodworkers from Big Sur to create walls covered with rippling sculptured wood and panels that pulsed with colored light in sync to the music, a décor Ralph Gleason likened to “a mural by Hieronymus Bosch.” Since it was a nightclub meant for drinking, and since their target clientele was underage, it failed to prosper.

Mother’s was precisely the sort of place that Luria Castel, Ellen Harmon, Jack Towle, and Alton Kelley wanted to avoid. They’d been in and around the Red Dog, and in their affinity for LSD, they harbored a certain contempt for alcohol (which was somehow okay in the saloon theater of the Red Dog but not otherwise). The four of them lived together at 1836 Pine Street, one of the four buildings that Bill Ham now managed, Kelley having discovered the place when he bought weed from a resident. Since everyone had a dog, it became known as the Dog House.

Kelley was a jack-of-all-trades and an extremely handy guy as well as a collagist and budding artist, a useful complement to Castel’s high-powered people-organizing skills left over from her W.E.B. Du Bois Club days. Collectively, they knew the scene and decided it would be fun to throw some dances. Castel knew about Longshoremen’s Hall through her political connections and her North Beach roots and booked a date for October 16 under the name Family Dog. Jack set up the bank accounts, Harmon answered the phone, and Kelley worked on a handbill.

Built in 1959, Longshoremen’s was a modern concrete building that had already hosted shows by Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie, and also “Teens and Twenties” dances—old-fashioned compared to what they planned. Promotion was fairly simple; they visited Ralph Gleason. Castel explained, and Gleason agreed, that San Francisco was “a pleasure city…[it] can be the American Liverpool…Dancing is the thing…they’ve got to give people a place to dance. That’s what’s wrong with those Cow Palace shows. THE KIDS CAN’T DANCE THERE. There’ll be no trouble when they can dance.” She was quite right.

One of their best ideas was to give each show a name. They were all comic book fans, so the first was A Tribute to Dr. Strange, which suggested to Gleason a “feast day or saint’s birthday and I thought at the time that a new religion was in the process of evolving.” It would present the two biggest bands in town, the Charlatans and Jefferson Airplane, as well as the Great Society, a band so new it would debut only the night before Dr. Strange at the Coffee Gallery on Grant Avenue. The Dog purchased a modest set of ads on Russ “the Moose” Syracuse’s popular KYA All Night Flight show, which brought him along as emcee. Marty Balin had also silk-screened three posters, which he posted at the Matrix and a couple of other cool places in town.

More than a thousand attended. They came in costumes—”velvet Lotta Crabtree to Mining Camp desperado, Jean Lafitte leotards, I. Magnin Beatnik, Riverboat Gambler, India Import Exotic”—wrote Gleason, decorated by lots of SNCC and peace buttons. The Charlatans were cowboys, and the Great Society’s Grace Slick wore a stylish miniskirt with grape-colored stockings. The only woman wearing makeup was Lynne Hughes, the Red Dog’s “Miss Kitty,” who also sang with the Charlatans.

Chet Helms walked in and was swept by an “exhilarating sense of safety, sanctuary. The feeling was ‘Well, they can’t bust us all.’ There was freedom and a moment of pure recognition. These were my people, my peers, all of a sudden together.” They danced, as the saying later had it, as though no one was watching. Spiritually just as much participants as hosts, the four members of the Family Dog had as good a time as everyone else.

The show also brought musicians together, which would inevitably lead to more music. John Cipollina was a rock guitarist from Marin County who came to Dr. Strange with his friend David Freiberg. They’d been in a band with a former coffeehouse folk singer named Dino Valenti (birth name Chester Powers), but Dino had been arrested for possession of pot not once but then a second time while awaiting trial. Consequently, he would be out of circulation for a while.

At the show, Cipollina and Freiberg, who both happened to be born under the sign Virgo, ruled by Mercury (also known as Quicksilver), met two more Virgos, Gary Duncan and Greg Elmore. Within days, they were all jamming at 1090, and Quicksilver Messenger Service came into being. Across the Bay in Berkeley, the mid-October anti-war Vietnam Day demonstrations gave birth to the Instant Action Jug Band, which would become Country Joe and the Fish.

A couple of weeks later, the Dog threw A Tribute to Sparkle Plenty. Thanks to good reviews from Gleason, the audience was even larger. The attendees included a band from Palo Alto then called the Warlocks, who in a few weeks would change their name to Grateful Dead. They’d spent the afternoon frolicking on Mount Tamalpais while enjoying some LSD and were still…elevated. When he saw the crowd—which was at least as high as he was—an extremely enthusiastic Phil Lesh braced Castel and said, “Lady, what this little séance needs is us.” He never spoke more truly.

By the fourth show, A Tribute to Ming the Merciless, which featured a band from Los Angeles, Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention, local and sometimes hostile teenagers began to come around. There were some fights and a glass door was broken, with Castel, not a small person, heroically chastising the hoods and serving as head of her own security. It was starting to be work.

On the same day as Ming, November 6, they had competition from a benefit for the San Francisco Mime Troupe’s legal defense fund, Appeal Party, in a loft behind the Chronicle building south of Market Street. Bill Graham, an erstwhile actor who’d been working for a construction firm, had become the business manager for the mime troupe. After overdoing it on the talent end, with acts from John Handy to the improvisational comedy troupe the Committee, Sandy Bull, Allen Ginsberg, the Fugs, and Jefferson Airplane (who happened to rehearse at the loft), Graham improvised brilliantly when the police arrived because the room was majestically oversold. “Frank [Sinatra] is flying in from Vegas!” Hundreds were still there at dawn. Graham saw that the real draw was the Airplane and made plans to throw a second benefit, in December. For that, he’d need a bigger room.

Early December saw the Rolling Stones perform in San Jose, Ken Kesey and his friends the Grateful Dead throw their second acid test, and Bob Dylan play both acoustic and electric sets in Berkeley.

The day after his show, Dylan went over to City Lights Bookstore to pose for pictures for his next album, with Allen Ginsberg and Michael McClure. The pictures went unused, although the album, Blonde on Blonde, was memorable. The photo shoot was unmistakably a symbolic passing of the torch, from Beat to a new generation. The word hippie had been in use for some while, by Bobby Darin in 1960, by Kenneth Rexroth in 1961, in a 1963 pop song by the Orlons named “South Street,” in Time in 1964, and soon, the meaning extremely unclear, by the New York Times in an article about an Omaha industrialist who owned racehorses.

In the near future, hippie would be set in stone; it was the people who listened to the newly electric music of Bob Dylan, the people now starting to fill the inexpensive flats of the Haight-Ashbury and the East Village. They largely called themselves freaks, from African American blues argot. But that was too edgy for the media, who wanted something softer, gentler. Hippies. It stuck. They were hippies.

The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties is available now through Da Capo.